How To EQ Vocals and De-Essing Techniques!

In the history of music, vocals have played a crucial role in many compositions.

From early Gregorian chants to your favorite song on the radio right now, a vocal can both characterize and carry a song and can often determine the public’s reaction to the song.

Why is this?

From trained musicians to casual music fans, a vocal immediately connects with a listener. The sound of the human voice naturally stands out to us, and lyrics can give a song meaning which sticks with the listener.

A sub-par instrumental can shine with a well-made vocal, and even a great instrumental can fall short if the vocal doesn’t drive it home.

With the importance placed on vocals, it’s key for them to sound right to achieve a professional sound. There are people who have made entire careers out of their ability to mix vocals, and the techniques to do so have become an artform all their own.

A lot of different steps go into perfectly mixing a vocal - such as compression and a good FX balance - but today we’ll just focus on the most important step, equalization (or EQ). In this article, we’ll cover the following topics as related to vocals:

By the end of this article you should have a better handle on this part of vocal mixing, and the context to dive further into the art of vocal production.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll be using FabFilter’s Pro-Q 2 equalizer.

Before going into the process of EQing vocals, it’s important to understand some common terms used to describe audio. Most of the words you’ll hear describe the frequency content of a sound, and whether there’s too much or too little going on in certain ranges of the frequency spectrum.

None of these terms really have a universally agreed-upon meaning, which can make dealing with them a bit confusing for early producers and mix engineers. Instead, they serve as hints pointing to where there might be an issue.

If someone says that something in your track sounds too “bright”, for example, you can check the highs for an issue, usually above 5 kHz. But the problem may be at 4 kHz. Use these terms to find the neighborhood of the problem, and pinpoint it from there.

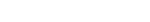

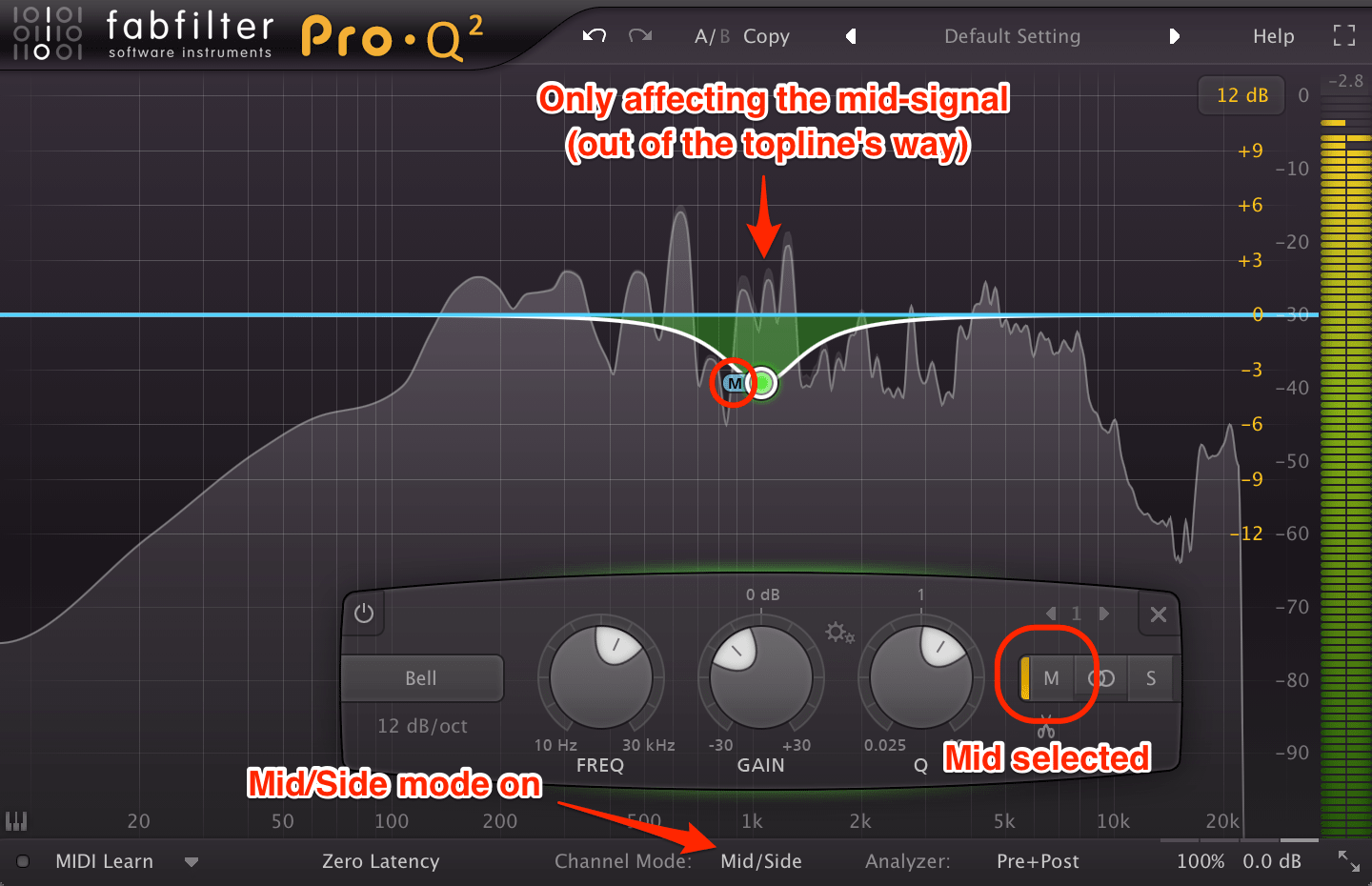

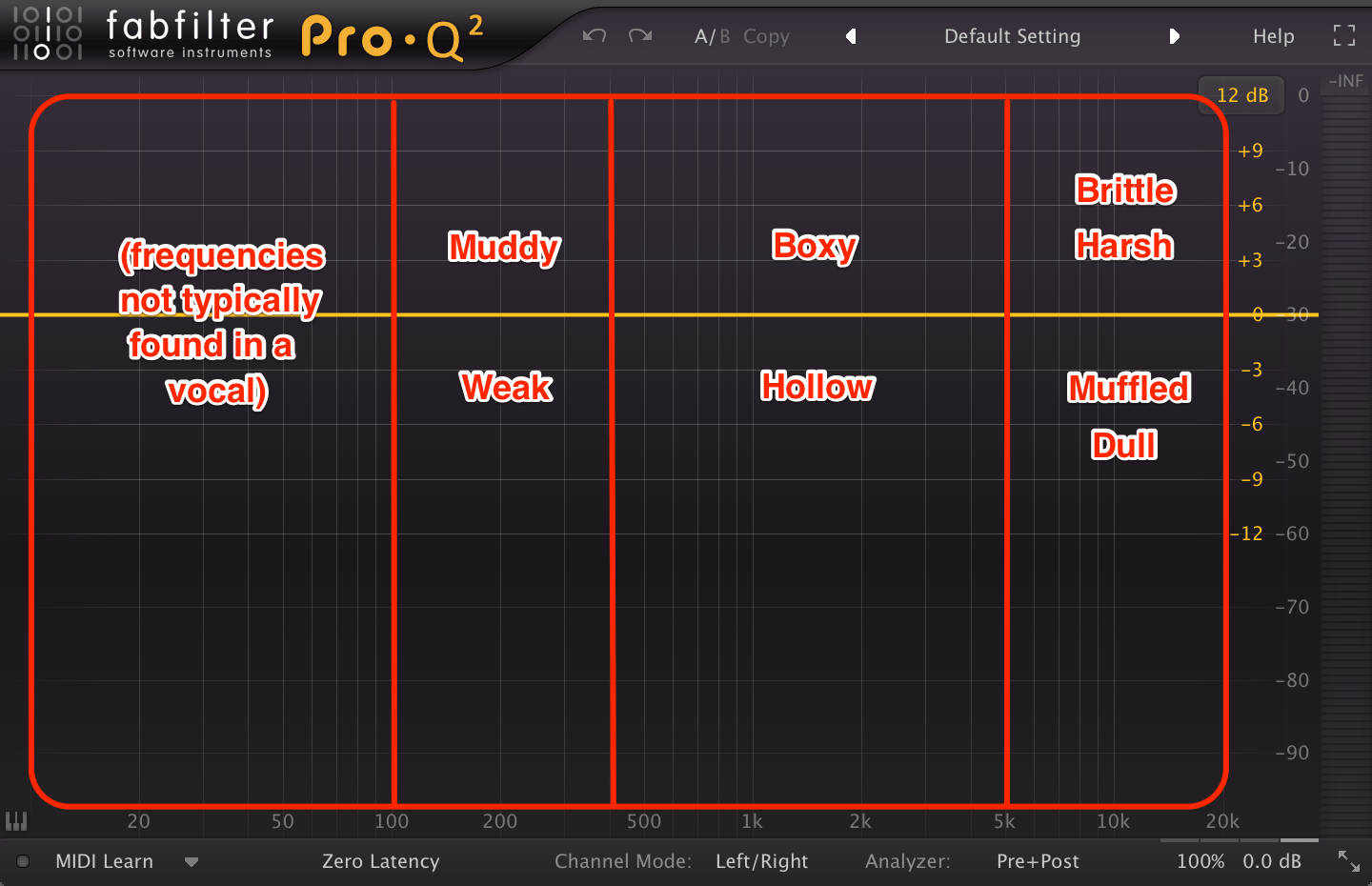

The following diagram shows some of these audio terms and their approximate ranges. Words above the center line (0 dB on Pro-Q 2) indicate that content here is too loud, and words under the line indicate content is too quiet.

The lowest frequencies of a vocal tend to be between 100 Hz and 400 Hz, depending on the vocalist. Female vocals naturally tend to start higher than male vocals, but treat each vocal uniquely.

This range provides much of the “body” and “weight” of the vocal. Overloading this frequency range can cause a vocal to sound “muddy” and unbalanced, while not having enough of this range can cause the vocal to sound “weak” and unsupported.

Some of the most important frequency content in a vocal occurs from 400 Hz to around 5 kHz. The human ear is naturally more attentive to this range, as it accounts for much of the sound energy in the human voice.

As a result, this range being too loud can be annoying, making the vocal sound “boxy”. Not enough level here can make the vocal sound “hollow”, and detract from its impact and presence in a mix.

A large part of a vocal’s clarity depends on frequency content in the highs, from around 5 kHz to the top of the frequency spectrum. These frequencies pop out in a mix, allowing the vocal to cut through other instruments that are simultaneously playing with it.

Not having these important frequencies can reduce this clarity, causing a vocal to sound “muffled” or “dull”. Loud and overloaded highs can result in a “brittle” or “harsh” sound which can become quite sharp to the ear.

Achieving a good balance here is key, and the easiest way to do this is to examine how the professionals do it.

You could perfectly understand the theory of EQing vocals, but this still isn’t enough if you don’t know how a well-balanced vocal sounds.

Constantly referencing professional tracks is the best way to do this. Actively listen to the frequency balance in the vocal. Note how the mix engineer is making space elsewhere in the track so the vocal can sit nicely.

It’s a great idea to do this referencing in your project while you’re mixing.

Bring an audio file of the reference track into your DAW on a new audio track. Toggle back and forth between your mix and the professional mix, and listen for differences. Your ears will reveal what you need to do!

Now that we’ve gotten the prep-work out of the way, let’s start EQing!

While we may commonly think of EQing as a step in the mixing process, EQing a vocal begins even earlier than that: during the recording. An EQ is just a chisel that we use to shape a sound, and we need a solid block of marble before we start chiseling.

The recording stage is the time to create that perfect block of marble. No amount of EQ will be able to fix a poorly recorded vocal, so consider the recording stage part of your EQing.

A huge part of this is microphone selection. Each microphone uniquely boosts and attenuates certain frequencies, creating what’s known as the mic’s frequency response.

Think of this as an EQ already boosting and cutting the vocal before it even enters your DAW.

Here are a few frequency response graphs for common microphones. The solid line shows emphasized or attenuated frequencies, with the dotted lines showing changes in the response depending on the distance from the microphone.

Notice how these mics each have different responses, and therefore have different uses. Before purchasing a new mic, be sure to look up its frequency response.

Audio-Technica AT4040

Shure SM57

Shure SM7B

Neumann U87

“Brighter” responses tend to be favorable, as the majority of popular music these days features vocals with a bit of high-frequency fizz. Again, remember that too much brightness can detract from a vocal and make it sound amateurish.

Microphone placement also has an impact on the frequencies that end up in the recording. If the vocalist sings close to the mic, lows can be emphasized. If the vocalist is far away from the mic, some lows and highs can drop out.

Having the vocalist sing from 5-8 inches away from the mic results in a nice, balanced recording. You can experiment with closer or farther mic placement for different sounds.

Incredibly, a lot of producers forget how important the performance is in terms of frequency content. If the vocalist sings monotonously and dully, it’ll take a lot more EQ work to brighten the vocal up.

You’re going to have to work with the performance you get, so be sure to get the take you want before even worrying about EQ.

Often times, the first plugin we insert on a vocal track is an EQ specifically used for cutting out unwanted frequencies. If there are frequency problems in the recording, it’s best to get rid of those first if possible.

There are going to be other plugins that come later in the chain, and generally we only want them to be reacting to the frequencies we want to keep. So, the first order of business is to cut those out using an EQ.

Keep in mind that, as the vocal moves from note to note, problem frequencies can move around too. The cuts you make will also affect different notes differently, as the EQ bands will stay in place when the vocal moves.

You can automate these bands to follow the frequencies you want to cut, or you can use a dynamic EQ to only cut these frequencies when it’s necessary. We’ll stick with standard EQ techniques for the sake of this article.

It’s usually a good idea to cut the deep lows out of a vocal. Even if the singer doesn’t go into this range, the mic may have picked up room noise that sits down there, which can eventually overlap with elements like the bass or synths in the final mix.

A smart way to do this is to play the vocal and find the lowest note that the vocalist sings. In the screenshot below, we’ve found the lowest note in the performance, with the lowest frequency (fundamental frequency) located at 300 Hz:

Because we know the vocal won’t go any lower than this, we can set up a high-pass filter just below it. This will cut out any unnecessary frequencies below the vocal while keeping the whole performance intact.

Be sure not to use too high of a Q on this HPF, as over-cutting can sterilize a mix and make it sound less professional. A slope of 12 dB / octave would work just fine. Be sure to reference other mixes and listen for how the vocal’s lows and mids are preserved and not overly cut.

Apart from cutting the lows, most other cuts should be done situationally - if there’s a specific problem that needs solving.

If you hear a problem but don’t know where in the frequency spectrum it is, create a bell filter with a high Q value and boost it quite high. Sweep this narrow boost slowly side to side.

Eventually, the issue frequency will be boosted and jump out. This is likely where you’ll need to cut.

The lows and low-mids could be a bit overpowering in a vocal recording, giving it a “muddy” sound. A simple bell filter with a low Q setting can be used to tame these.

Feel free to boost / attenuate as much as you need, but be sure not to go over the top. Keep using professional tracks as a reference for how the final vocal should sound.

You may hear a vocal described as “nasal”. This generally means that there are some resonant peaks of signal between 500 Hz and 3 kHz. This nasal quality is often just a characteristic of the singer’s voice, but can usually be handled quite easily.

Mic choice can fix this issue at the recording stage. Microphones that have a good amount of body and less boosting in the mids and high-mids can help. Shure’s SM7 or SM7B are solid options.

Mic placement can also help. Having the vocalist sing off-axis, or not directly into the mic, can cut down on these problems. Some engineers point the microphone down towards the singer’s neck or chest, which can reduce a voice’s nasal characteristic.

But with an EQ, the nasal frequency can just be treated like any other problem frequency. Use the sweeping bell filter technique to find the correct frequency and use a narrow bell filter to attenuate it. This should help take away that nasal sound.

Another problem that can come up when EQing vocals is sharp sibilance. Sibilance is the term used to categorize consonants that produce hissing sounds, like s, sh, ch, z, zh, and sometimes t.

These sounds can become overly loud in a recording because of how close the singer is to the microphone. Note that a pop filter won’t tame these, as they’re meant to soften plosives, sounds like b, d, g, p, and sometimes t and k.

We can use the bell filter technique to find sibilance and attenuate it, but we’ll go over some more reliable ways to deal with sibilance in the de-essing section.

Keep in mind that, usually, a compressor will follow the cutting EQ in a vocal processing chain. The compressor will probably bring up some of the cuts done in the EQ, so it’s up to you to keep tweaking these settings to get the desired balance.

After this compressor, or sometimes near the end of the chain, we introduce another EQ to boost some important frequencies.

Generally, you may want to take this opportunity to boost some of the highs, above around 5 kHz. This accentuates the consonant sounds in the vocal and gives it some “air”, making the vocal clearer and the lyrics easier to understand.

Depending on the sound of the vocal at this stage in the chain, the highs can be left alone or boosted a decent amount. If boosting is necessary, it’s a good idea to use a high shelf filter over a bell filter so resonant peaks aren’t created in the highs.

There are of course other ways to brighten up a vocal, including saturation, distortion, and harmonic excitation. All of these options can be considered, but EQ boosting is a viable way to do this.

Once again, reference professional tracks and note the brightness in the vocals.

You can even load up an EQ on the professional track and insert a high pass filter at around 5 kHz. This will momentarily isolate the highs, allowing you to hear how much high-frequency content the vocal has.

If it’s needed, we can also add a little boost around 1-2 kHz. As we mentioned before, this is the range most easily picked up by the human ear. If the vocal is still missing some presence with the highs boosted, a bit of a boost here can help improve the intelligibility.

Keep in mind that over-boosting here can cause the vocal to have the nasal sound that we’re generally avoiding.

Also keep in mind that the vocal is battling other elements in the mix for these frequencies. Even with a lot of boosting, the vocal will not cut through the mix if other elements are hogging those frequencies.

Sometimes the best way to improve the clarity of the vocal is to just EQ these frequencies out of other elements.

Any other boosts should be done situationally, only if you feel like the vocal needs them. Yet again, reference, reference, reference!

Remember that we said there are a few techniques to cut down overbearing sibilance? These processes are generally referred to as de-essing. Cutting down on these sharp sounds will soften the vocal and result in a more professional-sounding mix.

Again, we can somewhat start de-essing in the recording stage. Sibilance sounds are generally made by pressing air through the lips or tongue, so setting the mic up close to the vocalist’s mouth can accentuate them.

By angling the microphone a bit lower, toward the vocalists’ throat, we can decrease the sharpness of these sounds. The microphone, being angled off-axis from the singer’s mouth, won’t pick up sibilant sounds as much.

However, because there are other ways of dealing with sibilance after the recording, this isn’t so necessary. It’s possible to tame harsh sibilants with a normal mic setup, but this technique could help if your mic picks up a lot of highs.

We’ve already mentioned another way to deal with sibilance using an EQ. Simply use the bell filter technique to find the right frequency (usually between 3-10 kHz) and attenuate it with a narrow bell filter.

This isn’t the best way to fix the problem, however. By using an EQ, the frequency that we’re cutting will always be cut in the vocal, even when there aren’t any sibilant sounds happening. This can throw off the vocal’s sound, as these frequencies are still important to have.

A better, but more tedious solution is using gain automation. Slowly go through the vocal performance from beginning to end, decreasing the vocal’s level during sibilant sounds. Be sure to fine-tune the curve of the automation lines so the drop in level isn’t audible.

Gain automation is technically the clearest and most consistent form of de-essing. But tons of tiny volume automations can be a pain to set up, so thankfully we have access to plugins called de-essers. This is a quality vs. convenience choice, but both are viable.

Though there are some exceptions, a de-esser is generally a type of multiband compressor. Multiband compressors split the frequency spectrum into several bands, each of which have their own assigned compressor.

A de-esser splits the audio into several bands and focuses on the band containing the sibilance. Most will allow the user to set this split frequency. When the signal in this band crosses a threshold, compression is applied (like a normal compressor).

De-essers can generally be split-band or wideband. A split-band de-esser will just compress the high band when it’s activated, and a wideband de-esser will compress the whole signal when it’s activated.

Waves’ Renaissance DeEsser has both split-band and wideband modes, so it makes a great option for a de-essing plugin. It also offers a switch between a high-pass or band-pass filter to determine what frequencies are used for detection or split mode compression.

De-essers should generally be applied after compression in the processing chain. Placing one before a compressor will require much harder de-essing, as the compressor will bring these sibilants back up. After the last compressor or at the end of the chain are solid choices.

Most songs will contain a main vocal line (called the “topline”) and some background vocals. Because these have different purposes, they should be treated a bit differently when EQing.

The main vocal will generally be the most important element of a track. This is what listeners will remember, so it should be clear and sit nicely in the mix.

A huge part of achieving this is understanding the arrangement of your track. If there are four guitars and two keyboards and three synths all playing in the same range of frequencies as the vocal, nobody’s going to hear the vocal.

If there’s space in the arrangement for the vocal to shine through, there will be more space for it to fit into the mix.

Assuming the vocal has room to breathe, all of the EQ techniques that we’ve discussed so far can apply to the topline. It should be balanced and have a bit of brightness to cut through the mix.

It’s a good idea however, to make these adjustments without the vocal solo-ed.

We often go to affect a vocal (or any element in a track) with a mentality of: “I’m affecting this now, I need to hear it, I should solo the channel”. While this can help when cutting out trouble frequencies, final EQ decisions should be made with everything else playing too.

By soloing the vocal, we can lose sight of how it fits with the rest of the mix. We may think that it has way more room than it does and boost frequencies that eventually clutter the rest of the mix. Or we may over-cut frequencies that we actually needed to fill the mix out.

But given how important the topline is, it should fit into the mix like a puzzle piece. And the only way to do that is to see the rest of the puzzle.

With backing vocals however, we can EQ differently to help support the topline more, which is their main purpose.

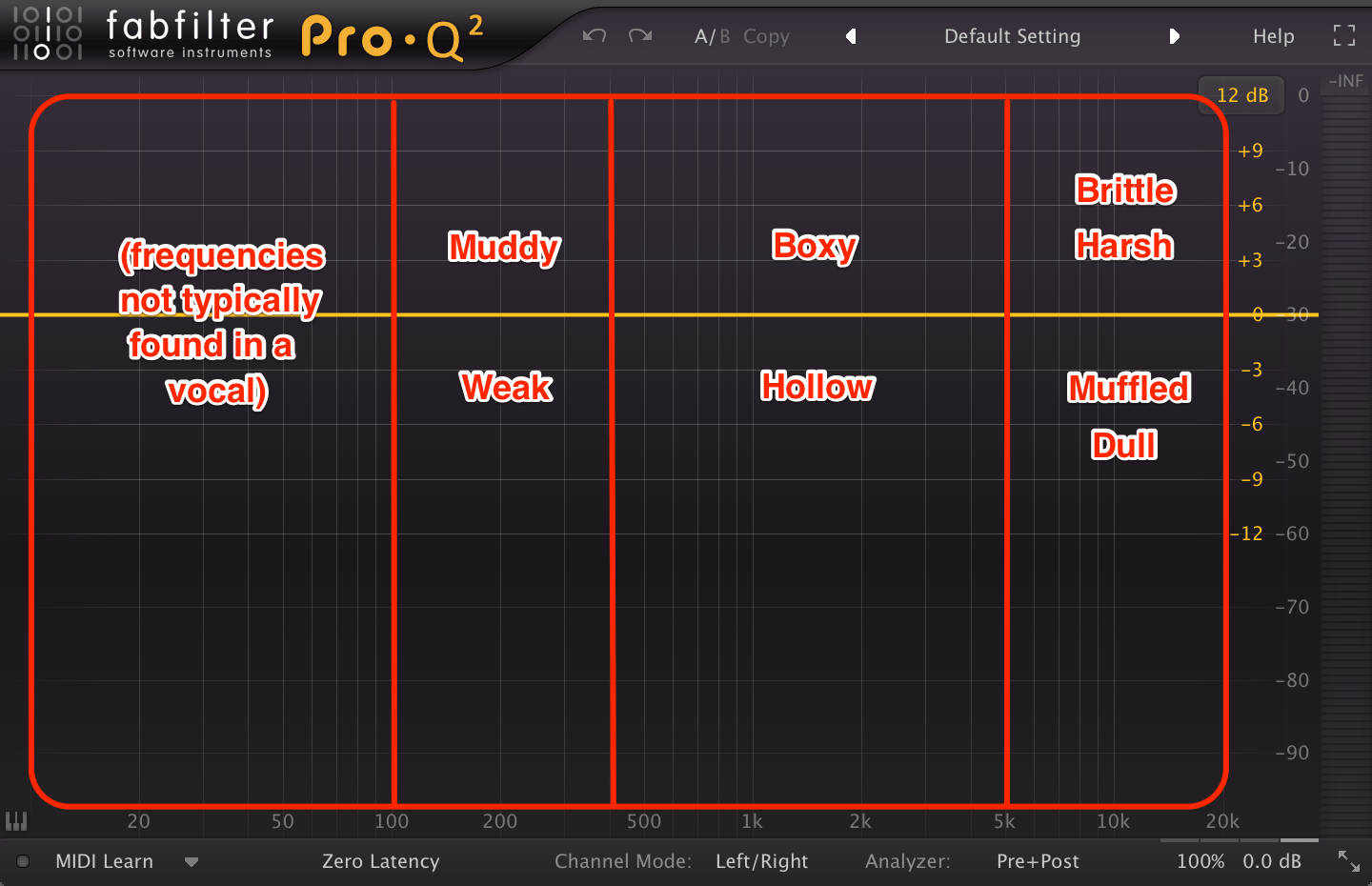

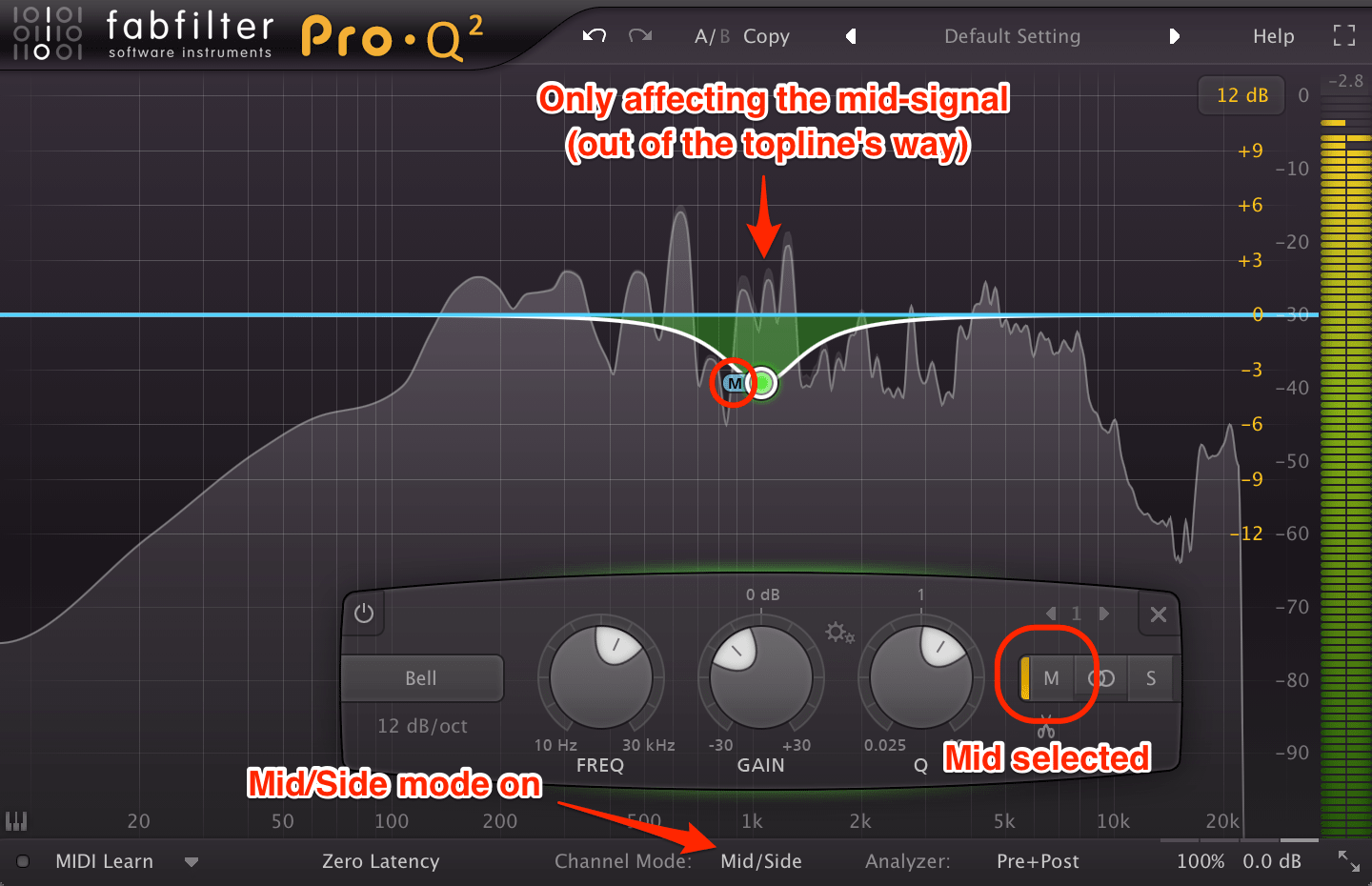

First of all, we can utilize some mid/side EQing to help the topline stand out among the background vocals.

Mid/side EQing allows us to separately apply EQ to the mid-signal (mono content of the signal) or the side-signal (stereo content of the signal).

Backing vocals are generally panned to the sides to make space for the topline in the center of the stereo field. However, if they’re not hard-panned (all the way to a side), the backing vocals may still have some mid-signal.

Using a spectrum analyzer (found on many EQ’s), we can find the most prominent frequencies in the topline. With that knowledge, we can use an EQ in mid/side mode and attenuate these frequencies in the center of the backing vocals.

This will allow the topline to have more space in the center and seemingly spread the backing vocals out of the way.

Background vocal channels can be separately affected in any of the ways we’ve mentioned so far, but affecting all of them together can help in situations like this one. This can be done through groups or buses, depending on the DAW you use.

Background vocals can also be high-passed a little bit higher to leave room for the body of the topline. Depending on the style, this can be done slightly or drastically, but either way can clear up space for the weight of the topline.

De-essing becomes particularly important when dealing with backing vocals. Regardless of talent, very few vocalists can sing a background part perfectly in time with the topline or other backing layers.

Because of this, consonant sounds may not line up with each other in the various takes. This is especially troublesome with sibilant sounds, as a bunch of out-of-time s’s or ch’s will immediately take attention away from the topline.

One solution is to just de-ess the backing vocals harder. Lower the threshold or range (depending on what de-esser you’re using) to get more attenuation. This will allow the topline to have the sibilant sounds without the backing vocals interfering.

If you’re using the gain automation de-essing technique, you can just lower the gain even more for these sibilants. Some engineers even completely cut out sibilant sounds from the backing vocals. Experiment and find what sounds best for the track.

EQ is one of the more important tools producers and engineers have for mixing, especially when dealing with vocals. The control that EQ’s offer allows us to work like surgeons, boosting and cutting to fit the vocal perfectly into the mix.

We can even use them to create differences between the main and background vocals. And with the help of de-essing we can prevent any of the vocals from being harsh and detracting from the mix.

But simply knowing some EQ techniques is only part of the story. Various EQ’s are comprised of different circuits and algorithms, ultimately resulting in different sounds. This is especially notable when dealing with hardware EQ’s or their software emulations, but it sitll applies to all EQ’s.

Most commercially available EQ’s sound good enough to use. But getting to know a couple will grant you more tools and options when EQing vocals or anything else.

We hope you enjoyed our article on Vocal EQing and De-essing. And now we want to hear from you!

Do you have any vocal EQing tips to share with other readers?

Feel free to leave them down below!

From early Gregorian chants to your favorite song on the radio right now, a vocal can both characterize and carry a song and can often determine the public’s reaction to the song.

Why is this?

From trained musicians to casual music fans, a vocal immediately connects with a listener. The sound of the human voice naturally stands out to us, and lyrics can give a song meaning which sticks with the listener.

A sub-par instrumental can shine with a well-made vocal, and even a great instrumental can fall short if the vocal doesn’t drive it home.

With the importance placed on vocals, it’s key for them to sound right to achieve a professional sound. There are people who have made entire careers out of their ability to mix vocals, and the techniques to do so have become an artform all their own.

A lot of different steps go into perfectly mixing a vocal - such as compression and a good FX balance - but today we’ll just focus on the most important step, equalization (or EQ). In this article, we’ll cover the following topics as related to vocals:

- Some audio vocab words and their meanings

- Referencing professional tracks

- EQing in the recording stage

- EQ cutting

- EQ boosting

- De-Essing

- Best practices for EQing the main vocal

- Best practices for EQing the backing vocals

By the end of this article you should have a better handle on this part of vocal mixing, and the context to dive further into the art of vocal production.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll be using FabFilter’s Pro-Q 2 equalizer.

Audio Vocab Words & Meanings

Before going into the process of EQing vocals, it’s important to understand some common terms used to describe audio. Most of the words you’ll hear describe the frequency content of a sound, and whether there’s too much or too little going on in certain ranges of the frequency spectrum.

None of these terms really have a universally agreed-upon meaning, which can make dealing with them a bit confusing for early producers and mix engineers. Instead, they serve as hints pointing to where there might be an issue.

If someone says that something in your track sounds too “bright”, for example, you can check the highs for an issue, usually above 5 kHz. But the problem may be at 4 kHz. Use these terms to find the neighborhood of the problem, and pinpoint it from there.

The following diagram shows some of these audio terms and their approximate ranges. Words above the center line (0 dB on Pro-Q 2) indicate that content here is too loud, and words under the line indicate content is too quiet.

The lowest frequencies of a vocal tend to be between 100 Hz and 400 Hz, depending on the vocalist. Female vocals naturally tend to start higher than male vocals, but treat each vocal uniquely.

This range provides much of the “body” and “weight” of the vocal. Overloading this frequency range can cause a vocal to sound “muddy” and unbalanced, while not having enough of this range can cause the vocal to sound “weak” and unsupported.

Some of the most important frequency content in a vocal occurs from 400 Hz to around 5 kHz. The human ear is naturally more attentive to this range, as it accounts for much of the sound energy in the human voice.

As a result, this range being too loud can be annoying, making the vocal sound “boxy”. Not enough level here can make the vocal sound “hollow”, and detract from its impact and presence in a mix.

A large part of a vocal’s clarity depends on frequency content in the highs, from around 5 kHz to the top of the frequency spectrum. These frequencies pop out in a mix, allowing the vocal to cut through other instruments that are simultaneously playing with it.

Not having these important frequencies can reduce this clarity, causing a vocal to sound “muffled” or “dull”. Loud and overloaded highs can result in a “brittle” or “harsh” sound which can become quite sharp to the ear.

Achieving a good balance here is key, and the easiest way to do this is to examine how the professionals do it.

Referencing Professional Tracks

You could perfectly understand the theory of EQing vocals, but this still isn’t enough if you don’t know how a well-balanced vocal sounds.

Constantly referencing professional tracks is the best way to do this. Actively listen to the frequency balance in the vocal. Note how the mix engineer is making space elsewhere in the track so the vocal can sit nicely.

It’s a great idea to do this referencing in your project while you’re mixing.

Bring an audio file of the reference track into your DAW on a new audio track. Toggle back and forth between your mix and the professional mix, and listen for differences. Your ears will reveal what you need to do!

EQing In The Recording Stage

Now that we’ve gotten the prep-work out of the way, let’s start EQing!

While we may commonly think of EQing as a step in the mixing process, EQing a vocal begins even earlier than that: during the recording. An EQ is just a chisel that we use to shape a sound, and we need a solid block of marble before we start chiseling.

The recording stage is the time to create that perfect block of marble. No amount of EQ will be able to fix a poorly recorded vocal, so consider the recording stage part of your EQing.

A huge part of this is microphone selection. Each microphone uniquely boosts and attenuates certain frequencies, creating what’s known as the mic’s frequency response.

Think of this as an EQ already boosting and cutting the vocal before it even enters your DAW.

Here are a few frequency response graphs for common microphones. The solid line shows emphasized or attenuated frequencies, with the dotted lines showing changes in the response depending on the distance from the microphone.

Notice how these mics each have different responses, and therefore have different uses. Before purchasing a new mic, be sure to look up its frequency response.

Audio-Technica AT4040

Shure SM57

Shure SM7B

Neumann U87

“Brighter” responses tend to be favorable, as the majority of popular music these days features vocals with a bit of high-frequency fizz. Again, remember that too much brightness can detract from a vocal and make it sound amateurish.

Microphone placement also has an impact on the frequencies that end up in the recording. If the vocalist sings close to the mic, lows can be emphasized. If the vocalist is far away from the mic, some lows and highs can drop out.

Having the vocalist sing from 5-8 inches away from the mic results in a nice, balanced recording. You can experiment with closer or farther mic placement for different sounds.

Incredibly, a lot of producers forget how important the performance is in terms of frequency content. If the vocalist sings monotonously and dully, it’ll take a lot more EQ work to brighten the vocal up.

You’re going to have to work with the performance you get, so be sure to get the take you want before even worrying about EQ.

EQ Cutting

Often times, the first plugin we insert on a vocal track is an EQ specifically used for cutting out unwanted frequencies. If there are frequency problems in the recording, it’s best to get rid of those first if possible.

There are going to be other plugins that come later in the chain, and generally we only want them to be reacting to the frequencies we want to keep. So, the first order of business is to cut those out using an EQ.

Keep in mind that, as the vocal moves from note to note, problem frequencies can move around too. The cuts you make will also affect different notes differently, as the EQ bands will stay in place when the vocal moves.

You can automate these bands to follow the frequencies you want to cut, or you can use a dynamic EQ to only cut these frequencies when it’s necessary. We’ll stick with standard EQ techniques for the sake of this article.

It’s usually a good idea to cut the deep lows out of a vocal. Even if the singer doesn’t go into this range, the mic may have picked up room noise that sits down there, which can eventually overlap with elements like the bass or synths in the final mix.

A smart way to do this is to play the vocal and find the lowest note that the vocalist sings. In the screenshot below, we’ve found the lowest note in the performance, with the lowest frequency (fundamental frequency) located at 300 Hz:

Because we know the vocal won’t go any lower than this, we can set up a high-pass filter just below it. This will cut out any unnecessary frequencies below the vocal while keeping the whole performance intact.

Be sure not to use too high of a Q on this HPF, as over-cutting can sterilize a mix and make it sound less professional. A slope of 12 dB / octave would work just fine. Be sure to reference other mixes and listen for how the vocal’s lows and mids are preserved and not overly cut.

Apart from cutting the lows, most other cuts should be done situationally - if there’s a specific problem that needs solving.

If you hear a problem but don’t know where in the frequency spectrum it is, create a bell filter with a high Q value and boost it quite high. Sweep this narrow boost slowly side to side.

Eventually, the issue frequency will be boosted and jump out. This is likely where you’ll need to cut.

The lows and low-mids could be a bit overpowering in a vocal recording, giving it a “muddy” sound. A simple bell filter with a low Q setting can be used to tame these.

Feel free to boost / attenuate as much as you need, but be sure not to go over the top. Keep using professional tracks as a reference for how the final vocal should sound.

You may hear a vocal described as “nasal”. This generally means that there are some resonant peaks of signal between 500 Hz and 3 kHz. This nasal quality is often just a characteristic of the singer’s voice, but can usually be handled quite easily.

Mic choice can fix this issue at the recording stage. Microphones that have a good amount of body and less boosting in the mids and high-mids can help. Shure’s SM7 or SM7B are solid options.

Mic placement can also help. Having the vocalist sing off-axis, or not directly into the mic, can cut down on these problems. Some engineers point the microphone down towards the singer’s neck or chest, which can reduce a voice’s nasal characteristic.

But with an EQ, the nasal frequency can just be treated like any other problem frequency. Use the sweeping bell filter technique to find the correct frequency and use a narrow bell filter to attenuate it. This should help take away that nasal sound.

Another problem that can come up when EQing vocals is sharp sibilance. Sibilance is the term used to categorize consonants that produce hissing sounds, like s, sh, ch, z, zh, and sometimes t.

These sounds can become overly loud in a recording because of how close the singer is to the microphone. Note that a pop filter won’t tame these, as they’re meant to soften plosives, sounds like b, d, g, p, and sometimes t and k.

We can use the bell filter technique to find sibilance and attenuate it, but we’ll go over some more reliable ways to deal with sibilance in the de-essing section.

Keep in mind that, usually, a compressor will follow the cutting EQ in a vocal processing chain. The compressor will probably bring up some of the cuts done in the EQ, so it’s up to you to keep tweaking these settings to get the desired balance.

EQ Boosting

After this compressor, or sometimes near the end of the chain, we introduce another EQ to boost some important frequencies.

Generally, you may want to take this opportunity to boost some of the highs, above around 5 kHz. This accentuates the consonant sounds in the vocal and gives it some “air”, making the vocal clearer and the lyrics easier to understand.

Depending on the sound of the vocal at this stage in the chain, the highs can be left alone or boosted a decent amount. If boosting is necessary, it’s a good idea to use a high shelf filter over a bell filter so resonant peaks aren’t created in the highs.

There are of course other ways to brighten up a vocal, including saturation, distortion, and harmonic excitation. All of these options can be considered, but EQ boosting is a viable way to do this.

Once again, reference professional tracks and note the brightness in the vocals.

You can even load up an EQ on the professional track and insert a high pass filter at around 5 kHz. This will momentarily isolate the highs, allowing you to hear how much high-frequency content the vocal has.

If it’s needed, we can also add a little boost around 1-2 kHz. As we mentioned before, this is the range most easily picked up by the human ear. If the vocal is still missing some presence with the highs boosted, a bit of a boost here can help improve the intelligibility.

Keep in mind that over-boosting here can cause the vocal to have the nasal sound that we’re generally avoiding.

Also keep in mind that the vocal is battling other elements in the mix for these frequencies. Even with a lot of boosting, the vocal will not cut through the mix if other elements are hogging those frequencies.

Sometimes the best way to improve the clarity of the vocal is to just EQ these frequencies out of other elements.

Any other boosts should be done situationally, only if you feel like the vocal needs them. Yet again, reference, reference, reference!

De-Essing

Remember that we said there are a few techniques to cut down overbearing sibilance? These processes are generally referred to as de-essing. Cutting down on these sharp sounds will soften the vocal and result in a more professional-sounding mix.

Again, we can somewhat start de-essing in the recording stage. Sibilance sounds are generally made by pressing air through the lips or tongue, so setting the mic up close to the vocalist’s mouth can accentuate them.

By angling the microphone a bit lower, toward the vocalists’ throat, we can decrease the sharpness of these sounds. The microphone, being angled off-axis from the singer’s mouth, won’t pick up sibilant sounds as much.

However, because there are other ways of dealing with sibilance after the recording, this isn’t so necessary. It’s possible to tame harsh sibilants with a normal mic setup, but this technique could help if your mic picks up a lot of highs.

We’ve already mentioned another way to deal with sibilance using an EQ. Simply use the bell filter technique to find the right frequency (usually between 3-10 kHz) and attenuate it with a narrow bell filter.

This isn’t the best way to fix the problem, however. By using an EQ, the frequency that we’re cutting will always be cut in the vocal, even when there aren’t any sibilant sounds happening. This can throw off the vocal’s sound, as these frequencies are still important to have.

A better, but more tedious solution is using gain automation. Slowly go through the vocal performance from beginning to end, decreasing the vocal’s level during sibilant sounds. Be sure to fine-tune the curve of the automation lines so the drop in level isn’t audible.

Gain automation is technically the clearest and most consistent form of de-essing. But tons of tiny volume automations can be a pain to set up, so thankfully we have access to plugins called de-essers. This is a quality vs. convenience choice, but both are viable.

Though there are some exceptions, a de-esser is generally a type of multiband compressor. Multiband compressors split the frequency spectrum into several bands, each of which have their own assigned compressor.

A de-esser splits the audio into several bands and focuses on the band containing the sibilance. Most will allow the user to set this split frequency. When the signal in this band crosses a threshold, compression is applied (like a normal compressor).

De-essers can generally be split-band or wideband. A split-band de-esser will just compress the high band when it’s activated, and a wideband de-esser will compress the whole signal when it’s activated.

Waves’ Renaissance DeEsser has both split-band and wideband modes, so it makes a great option for a de-essing plugin. It also offers a switch between a high-pass or band-pass filter to determine what frequencies are used for detection or split mode compression.

De-essers should generally be applied after compression in the processing chain. Placing one before a compressor will require much harder de-essing, as the compressor will bring these sibilants back up. After the last compressor or at the end of the chain are solid choices.

EQing The Main Vocal

Most songs will contain a main vocal line (called the “topline”) and some background vocals. Because these have different purposes, they should be treated a bit differently when EQing.

The main vocal will generally be the most important element of a track. This is what listeners will remember, so it should be clear and sit nicely in the mix.

A huge part of achieving this is understanding the arrangement of your track. If there are four guitars and two keyboards and three synths all playing in the same range of frequencies as the vocal, nobody’s going to hear the vocal.

If there’s space in the arrangement for the vocal to shine through, there will be more space for it to fit into the mix.

Assuming the vocal has room to breathe, all of the EQ techniques that we’ve discussed so far can apply to the topline. It should be balanced and have a bit of brightness to cut through the mix.

It’s a good idea however, to make these adjustments without the vocal solo-ed.

We often go to affect a vocal (or any element in a track) with a mentality of: “I’m affecting this now, I need to hear it, I should solo the channel”. While this can help when cutting out trouble frequencies, final EQ decisions should be made with everything else playing too.

By soloing the vocal, we can lose sight of how it fits with the rest of the mix. We may think that it has way more room than it does and boost frequencies that eventually clutter the rest of the mix. Or we may over-cut frequencies that we actually needed to fill the mix out.

But given how important the topline is, it should fit into the mix like a puzzle piece. And the only way to do that is to see the rest of the puzzle.

EQing Backing Vocals

With backing vocals however, we can EQ differently to help support the topline more, which is their main purpose.

First of all, we can utilize some mid/side EQing to help the topline stand out among the background vocals.

Mid/side EQing allows us to separately apply EQ to the mid-signal (mono content of the signal) or the side-signal (stereo content of the signal).

Backing vocals are generally panned to the sides to make space for the topline in the center of the stereo field. However, if they’re not hard-panned (all the way to a side), the backing vocals may still have some mid-signal.

Using a spectrum analyzer (found on many EQ’s), we can find the most prominent frequencies in the topline. With that knowledge, we can use an EQ in mid/side mode and attenuate these frequencies in the center of the backing vocals.

This will allow the topline to have more space in the center and seemingly spread the backing vocals out of the way.

Background vocal channels can be separately affected in any of the ways we’ve mentioned so far, but affecting all of them together can help in situations like this one. This can be done through groups or buses, depending on the DAW you use.

Background vocals can also be high-passed a little bit higher to leave room for the body of the topline. Depending on the style, this can be done slightly or drastically, but either way can clear up space for the weight of the topline.

De-essing becomes particularly important when dealing with backing vocals. Regardless of talent, very few vocalists can sing a background part perfectly in time with the topline or other backing layers.

Because of this, consonant sounds may not line up with each other in the various takes. This is especially troublesome with sibilant sounds, as a bunch of out-of-time s’s or ch’s will immediately take attention away from the topline.

One solution is to just de-ess the backing vocals harder. Lower the threshold or range (depending on what de-esser you’re using) to get more attenuation. This will allow the topline to have the sibilant sounds without the backing vocals interfering.

If you’re using the gain automation de-essing technique, you can just lower the gain even more for these sibilants. Some engineers even completely cut out sibilant sounds from the backing vocals. Experiment and find what sounds best for the track.

Conclusion

EQ is one of the more important tools producers and engineers have for mixing, especially when dealing with vocals. The control that EQ’s offer allows us to work like surgeons, boosting and cutting to fit the vocal perfectly into the mix.

We can even use them to create differences between the main and background vocals. And with the help of de-essing we can prevent any of the vocals from being harsh and detracting from the mix.

But simply knowing some EQ techniques is only part of the story. Various EQ’s are comprised of different circuits and algorithms, ultimately resulting in different sounds. This is especially notable when dealing with hardware EQ’s or their software emulations, but it sitll applies to all EQ’s.

Most commercially available EQ’s sound good enough to use. But getting to know a couple will grant you more tools and options when EQing vocals or anything else.

We hope you enjoyed our article on Vocal EQing and De-essing. And now we want to hear from you!

Do you have any vocal EQing tips to share with other readers?

Feel free to leave them down below!

Do you want to get a jump start in Ableton Live?

Download our free Ableton Starter Pack and get level up your production today!

(2 Ableton Project Files & 300 Drum Samples + Loops)

(2 Ableton Project Files & 300 Drum Samples + Loops)